Like all online topics these days, coding agents are divisive. Some zealots predicted the end of the software developer around 8 months ago. Others consider those agents to be as useless and atrocious as Microsoft Teams. Most of us are somewhere on the spectrum between those extremes.

Over the last few weeks, I have been taking advantage of Anthropic’s holiday offerings and have been spending an unhealthy amount of time with Claude Code. It’s fun, it’s productive, but it also teaches us something about the state of the art. Or rather: about the perceived state of the art.

Coding agents generate their code based on natural language, and that, by definition, is open to interpretation. As a result, the agent doesn’t always do what we thought we asked — it does what the LLM interprets our prompt to mean. That leads to something akin to creativity: the AI generates something that genuinely surprises us.

This “emergent behaviour” is the result of the agentic workflow. It’s not one prompt, but a chain reaction of prompts, reasoning, verification, and tweaks. Like a game of Chinese Whispers, these LLMs amplify parts of their message until a surprising result comes out.

Let me walk through a few examples.

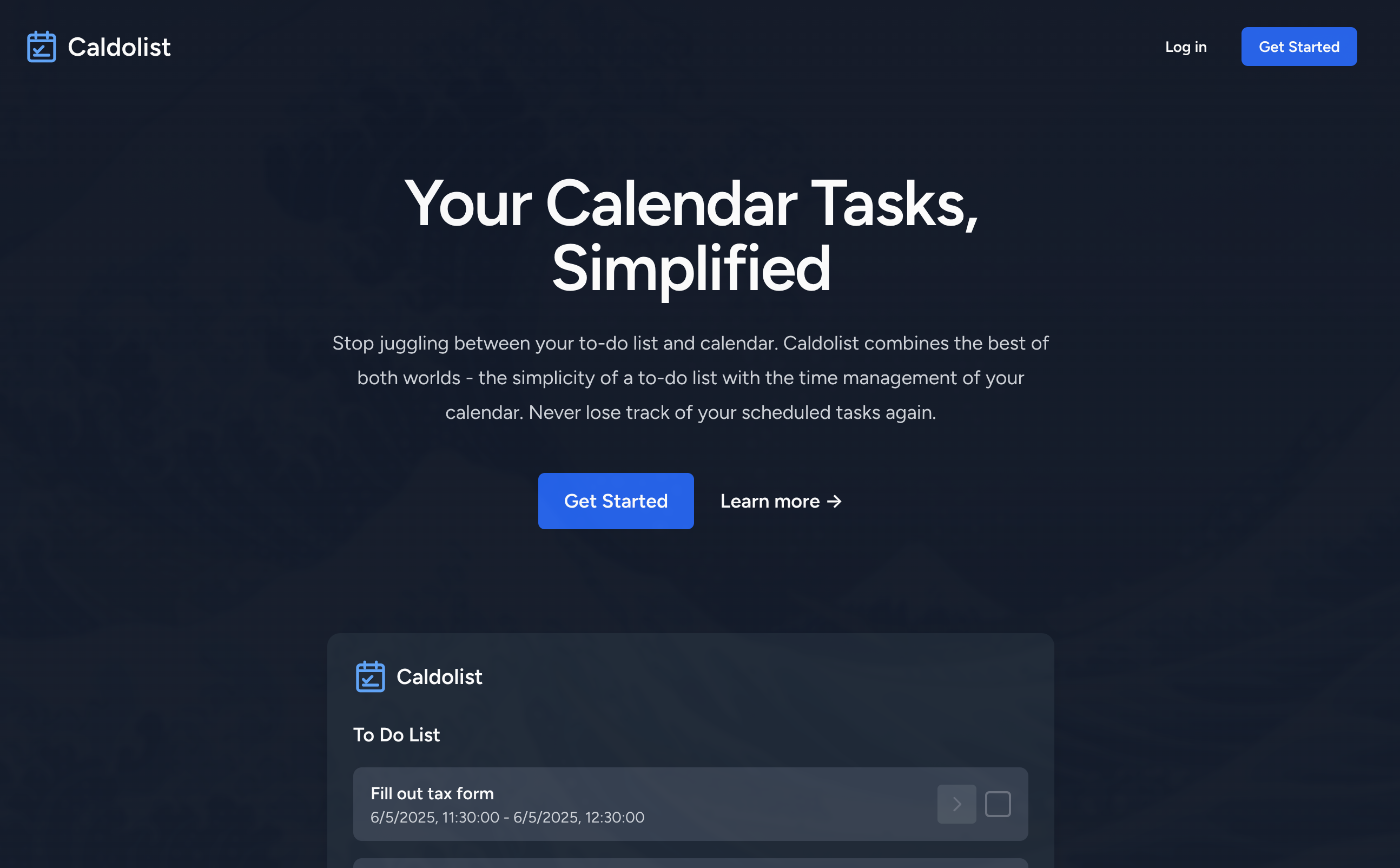

Landing page magic

For one of my apps, I asked Claude to generate a home page, and it generated a fine, albeit bland result. I don’t remember the exact prompt, but it was a high-level one-liner. “Replace the current home page with one that explains the product.”

When you look at the result, it’s easy to miss a case of emergent behaviour: it includes support for Dark/Light mode. I never specified that! But the agentic chain reaction in Claude Code examined its training data and concluded that, in 2026, every landing page needs to go dark for the right people. This is the most straightforward kind of example: Claude adds basic, run-of-the-mill functionality without being asked.

Artistic choices

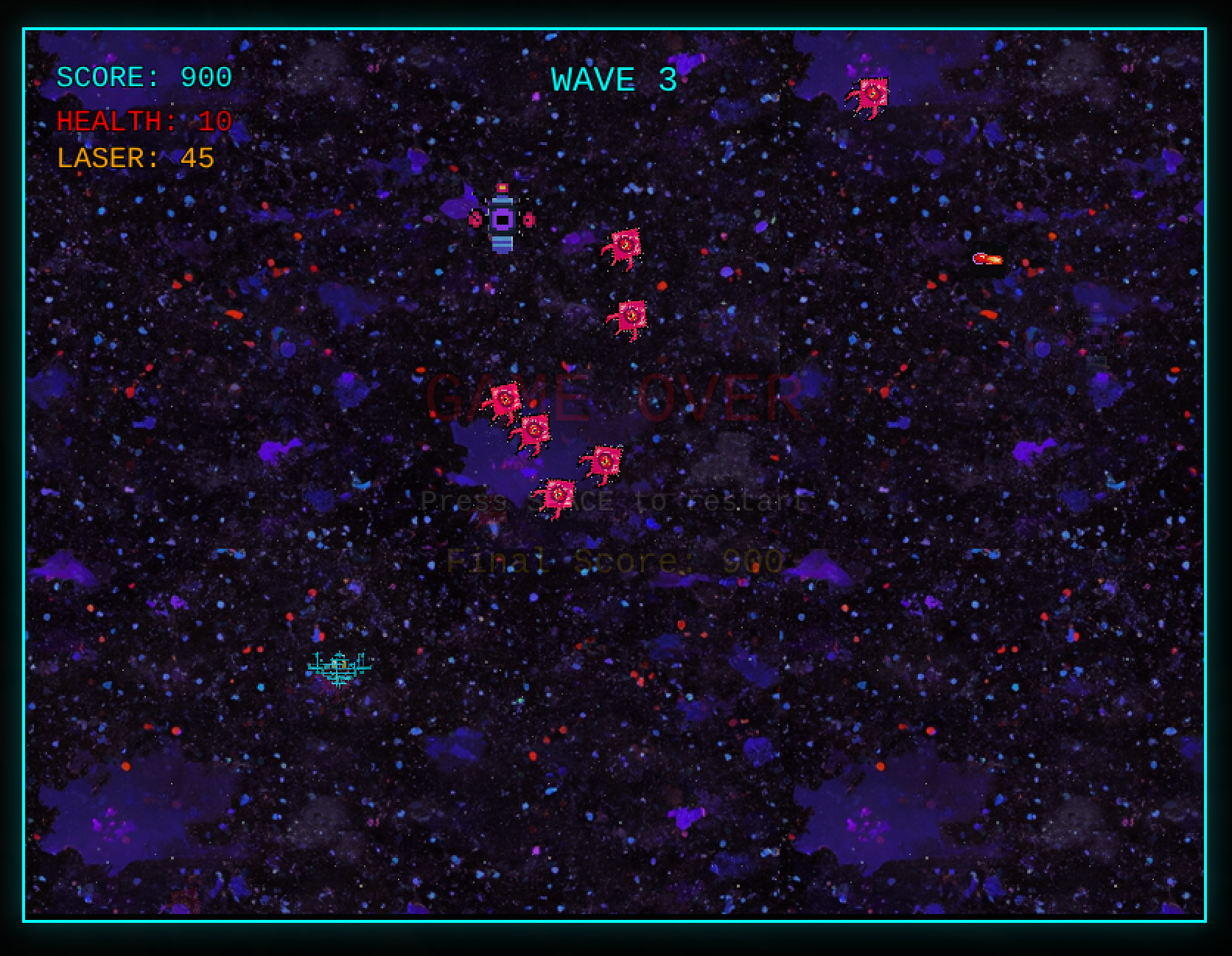

Vibe coding’s big breakthrough came with Pieter Level’s flight simulator game. It was the purest form of this new creative flow: we tell the computer what to add rather than how to do that. So, whenever a model claims a new level of autonomy, I vibe-code a game to see how much better it got.

Neon Void is as vibe-coded as it can get. I didn’t even pick a tech stack. All I did was describe the changes I wanted to see in the game. Claude generated the code, but it also prompted DALL-E to generate the graphics. And that leads to very interesting “emergent behaviour”. What stands out to me is how well these graphics fit together. Sure, it will not win Game Of The Year, but the different enemy types all feel like they belong in the game. Nothing stands out in a bad way.

The reason is straightforward but magical: Claude used a similar prompt for each of the sprites. If I were to prompt it to “add a third type of enemy”, it would create another spaceship in the same style. It would not add a dinosaur. The game of Chinese Whispers has created some kind of Art Director. Emergent behaviour.

Unique features

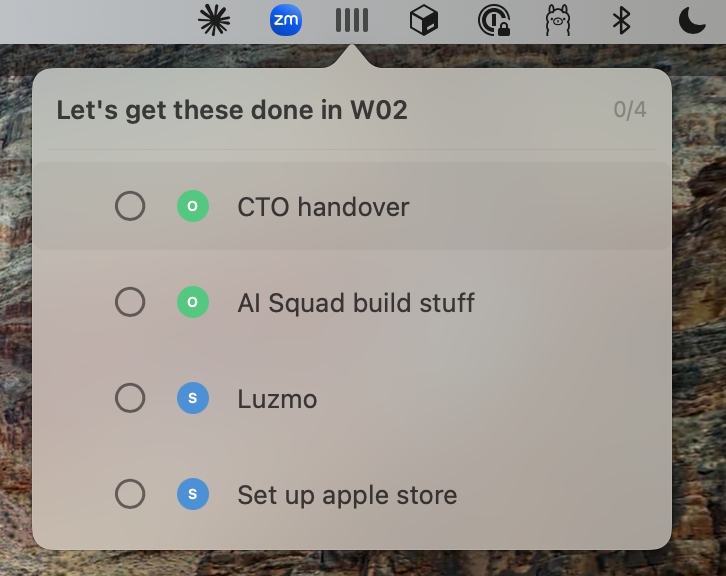

One thing I’ve wanted to try for a long time is creating a native macOS app. The learning curve had stopped me until Claude took it away. Every Monday, I paste 4 Post-it notes on my monitor with the “big things” I want to get done that week. Claude helped me build a menu bar app for that.

When building a feature, I rely heavily on Claude’s Plan Mode. The prompt generates a plan of attack rather than code. And often, Claude will ask questions to refine said plan.

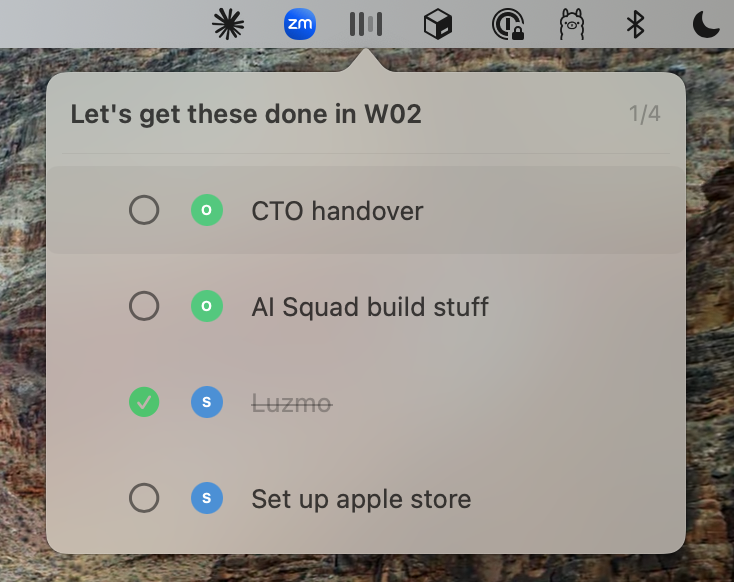

When I prompted to “replace the menu bar icon with something that matches the logo”, Claude asked whether I wanted a one-on-one copy of the logo or “something else”. I picked the intriguing option, and after a bit of back and forth, it proposed to adapt the icon to the state of the app. When Post-it 3 was marked as Done, the third line in the icon would be greyed out.

The menu icon has 4 bars left to do.

Now the icon only has three bars because I finished a goal.

That’s the kind of stuff designers and PMs geek out about! Through this emergent behaviour in Plan Mode, Claude gave me a cute, unique feature to add to the app. One I wouldn’t have spent time on myself.

The insight

Now, back to the perception of the state of the art. I love these little surprises and easter eggs. It’s extremely productive to ship a landing page without worrying about details like Dark Mode. But I’m a CTO. I’m used to delegating. I love delegating.

The average engineer doesn’t. For most of them, Claude might be the first time they have to care about the outcome, not the output. That’s a rough shift in mindset.

When I ask an engineer to add a database, I don’t really care if it’s MySQL or Postgres. I will challenge it if they pick Clickhouse, but in general, I no longer feel the need to intervene in these basic choices. It’s all the same result.

So, when Claude throws in another

That could be a very good explanation as to why so many coders loathe coding agents — why they feel AI-generated code is bad.

What if they just struggle with delegation?

It would explain why so many founders, indie hackers, CTOs and engineering managers are enamoured with coding agents. To them, it feels like they have an infinite number of developers on tap. They care about the outcome, not the details.

To engineers who are used to coding in isolation, it feels like pair programming 24/7 with a partner who does everything just slightly wrong. It’s a frustrating experience.

The future belongs to those who learn the noble art of delegation, but combine that with the critical technical eye. Engineers who just accept everything Claude throws at them will generate unmaintainable products. But developers who nitpick every implementation detail because “that’s not how I would do it” are equally destructive. They needlessly slow down the delivery process while the competition catches up.

If toying around with coding agents has taught me one thing this winter, it’s this: the engineer of the future needs to know how to delegate to an agent and review the result with a critical, but pragmatic eye.

Anything else belongs to the past.